Meet The Firms looked a bit different than usual this year. There were masks, social distancing and virtual meet-and-greets, but the meaningful interactions were the same.

Meet The Firms looked a bit different than usual this year. There were masks, social distancing and virtual meet-and-greets, but the meaningful interactions were the same.

Nearly four dozen UCA accounting students met and discussed their futures with 16 firms from across the state and region Sept. 17.

Students shared their stories, talked about what attracted them to accounting, discussed their aspirations were. Firms shared career and internship opportunities, gave insight into their company cultures and quizzed students on what areas of accounting interested them for their careers.

The event is open to all accounting majors and members of Beta Alpha Psi and the Accounting Club. It is a crucial event for students to secure internships and explore career opportunities following graduation.

Participating firms included: Hudson Cisne & Co., Landmark, ArcBest, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, Inuvo, Erwin & Co., Dassault Falcon Jet, HoganTaylor, Bell & Co., Onyx Brands, Arkansas Department of Finance & Administration, Acxiom, PwC, Windstream, Frost, EGP and BKD.

The University of Central Arkansas College of Business has hired two faculty members in its

The University of Central Arkansas College of Business has hired two faculty members in its

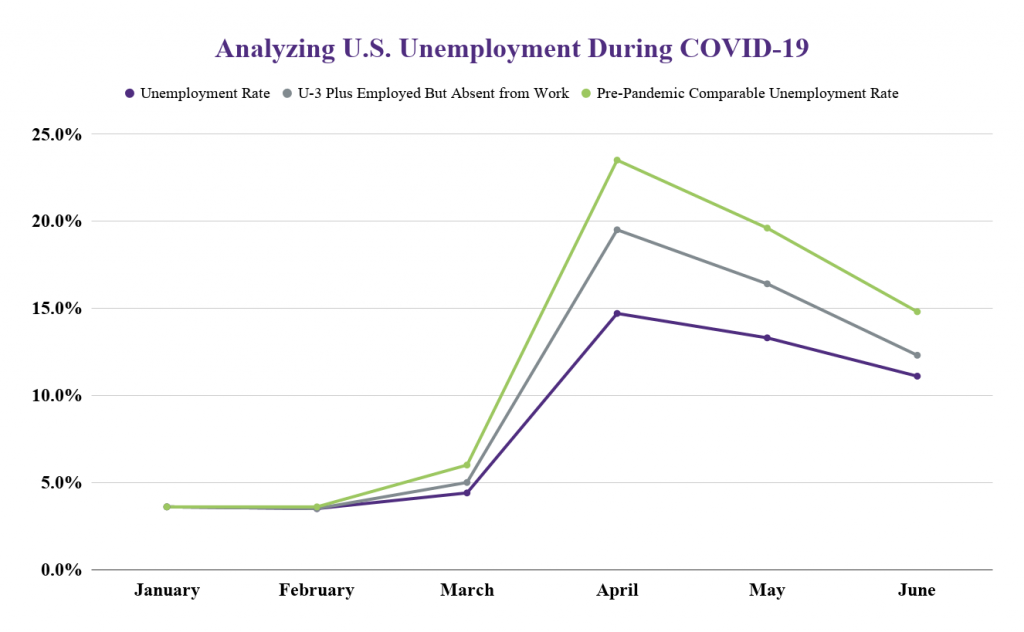

By Jeremy Horpedahl, Ph.D.

By Jeremy Horpedahl, Ph.D.

Japan is one of the world’s most advanced and largest economies, yet lags behind in its use of e-payment and e-commerce.

Japan is one of the world’s most advanced and largest economies, yet lags behind in its use of e-payment and e-commerce. Cynthia Burleson, director of the Center for Insurance & Risk Management in the UCA College of Business, was featured in June on an episode of the Insurance Town podcast.

Cynthia Burleson, director of the Center for Insurance & Risk Management in the UCA College of Business, was featured in June on an episode of the Insurance Town podcast.

Hannah Robinson, a senior

Hannah Robinson, a senior