This section, along with the other 11 chapters on the most important parts of the Arkansas economy, are authored by Jeremy Horpedahl, an ACRE scholar and assistant professor of economics at the University of Central Arkansas; Amy Fontinelle, author and editor of hundreds of public policy works; and Greg Kaza, Executive Director of the Arkansas Policy Foundation.

This section is a chapter in a larger work – The Citizen’s Guide to Understanding Arkansas Economic Data.

What are personal income, per capita personal income, and disposable personal income in Arkansas?

Personal income is the total income people receive from all sources, both domestic and international. Sources of personal income include:

• labor, such as wages, salaries, tips, bonuses,and supplements to wages and salaries such as contributions to employee pension and insurance funds;

• proprietors’ income from owning a home or business;

• income produced by financial assets such as dividends, interest, and rent; and

• government benefits,such as Social Security benefits, medical benefits, veterans’ benefits, and unemployment insurance.

The US Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) reports personal income.1 Arkansas’s total 2017 personal income was $122.5 billion, which ranked 34th nationally before adjusting for population.2

Per capita personal income is simply the total state personal income divided by the number of people in the state. In 2017, Arkansas’s population was 3,004,279 (32nd in the nation) as reported by the US Census Bureau. Its per capita personal income was $40,791 (43rd in the nation).3

Disposable personal income is the money available to individuals and households for uses such as spending and saving after they’ve paid their personal income taxes. It is calculated as personal income minus personal current taxes paid to federal, state, and local governments.4 As with personal income, it is also useful to look at disposable personal income on a per capita basis by dividing it by the population. Disposable personal income per capita in Arkansas was $36,786 in 2017.

Why are personal income measures important to Arkansans?

State governments use personal income data to measure the economic base for planning purposes, such as how much tax revenue they can generate with income taxes. The federal government uses state personal income data to allocate federal aid and matching grants to the states. Most of these funds go to health care; the rest go to welfare programs, transportation, community and regional development, education, job training, employment, and social services.5

Another use of personal income data involves state spending limits. According to the BEA, 19 states have constitutional or statutory limits on state government taxes and spending that are tied to state personal income or one of its components. These states account for more than one-half of the US population, though Arkansas is not one of these states (Arkansas is one of 20 states with no explicit tax or expenditure limits).

When disposable personal income increases, consumer spending increases. Arkansas businesses may perform better when residents have more money to spend on everything from restaurant meals to new cars. Businesses, in turn, have more revenue to reinvest. They can afford to hire more workers, purchase more goods and services from other businesses, and buy back shares from or pay dividends to shareholders (in the case of publicly traded companies).

The BEA breaks down personal income by industry. By looking at how personal income is changing in each industry, we can get a better idea of what’s happening in Arkansas’s economy and how it compares to what’s happening in the United States as a whole. And knowing which industries are growing and which are shrinking can help people make better decisions about what educational and career choices to pursue or where to invest in new businesses.

Using the four quarters of data from the fourth quarter of 2016 to the fourth quarter of 2017 (the latest available at the time of writing), these are the five private, nonfarm industries with the fastest-growing earnings in Arkansas:

• professional,scientific,and technical services (5.9%)

• educational services (5.2%)

• wholesale trade (5.1%)

• durable goods manufacturing (4.8%)

• construction (4.7%)

The same list for the nation as a whole is very different, with only construction appearing in the top five for both Arkansas and the United States.6 To catch up to Missouri, Arkansas’s total personal income would need to increase by $5.6 billion, or 5.1%. To catch up to Texas, it would need to increase by $16.1 billion, or 14.6%.

What’s not included in personal income?

Personal income may provide an incomplete picture of an individual’s true income because it doesn’t capture people’s ability to spend money by using savings or borrowing. It does not include capital gains or losses, for example.7 An individual could make $150,000 from the sale of a house and this sum would not be reflected in personal income. Also not included are personal contributions for social insurance, income from government employee retirement plans, income from private pensions and annuities, and income from interpersonal transfers, such as child support and alimony.8

The shortcomings of personal income carry over to per capita personal income and disposable personal income. Disposable personal income is further distorted by the fact that even though it doesn’t include the capital gains people earn when they sell assets that have increased in value, it does include any capital gains taxes a person might have paid. Disposable personal income also doesn’t include the accumulation of wealth (i.e., savings) that people can use to support their spending.9

What is the trend in Arkansas’s personal income?

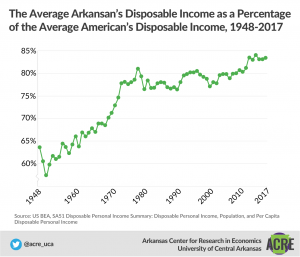

Real per capita disposable personal income in Arkansas has increased steadily since the late 1940s, with temporary drops during US recessions. It has grown from $8,523 in 1948 to $36,786 in 2017 (in inflation-adjusted dollars). In the 1950s, this measure averaged just 62% of the national level, but by the late 1970s, it was up to 80% of the national level, where it has roughly stayed since then (it was 83.4% in 2017). Prior to 2012, Arkansas rarely ranked higher than 47th in the nation, and often 49th. But since 2012, Arkansas’s rank has been 41st, 42nd, or 43rd.10

Within Arkansas’s metropolitan areas, per capita personal income in 2016 was highest in Northwest Arkansas at $55,729 (the Fayetteville-Springdale-Rogers area). Per capita personal income was lowest in Pine Bluff, at $32,227—number 376 out of the country’s 382 metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs).

Why is there such a big difference in income between these two areas? The answer is complex, but in short, Northwest Arkansas has benefited from the decades-long presence of several Fortune 500 companies and, more recently, from many startup businesses. Pine Bluff has been losing both people and businesses in recent years, making economic growth difficult. But the question of “Why?” is very complex.

The largest MSA in Arkansas, Little Rock (including North Little Rock, Conway, and the surrounding communities), was in the middle, at $42,582. For Arkansans living outside the wealthier areas in Arkansas, the numbers are much lower. If we eliminate Northwest Arkansas counties and the Little Rock metropolitan area, per capita income drops from $39,722 to $33,549.11

Footnotes:

1 US Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), “State Personal Income and Employment: Concepts, Data Sources, and Statistical Methods,” September 2016, https://bea.gov/regional/pdf/spi2015.pdf.

2 BEA, “Personal Income for Arkansas,” March 22, 2018, https://www.bea.gov/regional/bearfacts/action.cfm?geoType=3&fips=05000&areatype=05000.

3 Ibid.

4 BEA, “A Guide to the National Income and Product Accounts of the United States,” https://www.bea.gov/national/pdf/nipaguid.pdf, accessed January 3, 2019.

5 Norton Francis et al., “What Types of Federal Grants Are Made to State and Local Governments and How Do They Work?” The Tax Policy Center’s Briefing Book (Washington, DC: Tax Policy Center, n.d., ca. 2015), http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/briefing-book/what-types-federalgrants-are-made-stateand-local-governments-and-how-do-they-work, accessed January 17, 2018.

6 Interested readers can locate the data we used by going to BEA’s Interactive Data at https://www.bea.gov/itable/, selecting “GDP & Personal Income” under “Regional Data,” clicking “Begin using the data,” and following these steps: (1) select “Quarterly State Personal Income”; (2) select “Personal Income by Major Component and Earnings by Industry (SQ5, SQ5H, SQ5N)”; (3) select “NAICS”; (4) select “Arkansas” for “Area,” “Compound annual growth rate between any two periods” for “unit of measure,” and “All statistics in table” for “statistic”; (5) select “2016:Q4” to “2017:Q4”; then (6) see the section “Earnings by Industry.”

7 John Ruser, Adrienne Pilot, and Charles Nelson, “Alternative Measures of Household Income: BEA Personal Income, CPS Money Income, and Beyond,” working paper prepared for presentation to the Federal Economic Statistics Advisory Committee on December 14, 2004, https://www.bea.gov/about/pdf/AlternativemeasuresHHincomeFESAC121404.pdf.

8 Ibid., p. 6.

9 Ibid.

10 US BEA, SA51 Disposable Personal Income Summary: Disposable Personal Income, Population, and Per Capita Disposable Personal Income.

11 US BEA, CA1 Personal Income Summary: Personal Income, Population, Per Capita Personal Income. Note: 2017 data have not yet been released for MSAs and counties as of this writing.

There are 12 main chapters in the book, each detailing and explaining and important part of the Arkansas economy. They are Median Household Income; Fortune 500 Companies; Economic Freedom; Personal Income; Wages; Poverty; Migration; Education Attainment; Government Revenue and Spending; Total Nonfarm Payroll Employment; Gross Domestic Product; Unemployment and Labor Force Participation

These 12 chapters were written by expert authors, including: Jeremy Horpedahl, an ACRE scholar and assistant professor of economics at the University of Central Arkansas; Amy Fontinelle, author and editor of hundreds of public policy works; and Greg Kaza, Executive Director of the Arkansas Policy Foundation.

If you are interested in sharing your thoughts and questions about Arkansas’s economy, we would love to hear from you. You can email ACRE at acre@uca.edu, tweet Dr. Jeremy Horpedahl, at @jmhorp, or comment on ACRE’s Facebook page.

If you would like a printed copy for your own home or office, please email acre@uca.edu with the subject line Printed Citizen’s Guide, and include your name, your organization’s name, and your address.