By Dr. Jeremy Horpedahl

Arkansas has the third highest combined state and local tax rate in the nation. How did this happen? Research we are conducting at the Arkansas Center for Research in Economics suggests that part of the reason is that many counties and cities have elected to increase their own sales tax rates. Since 1981, local governments in Arkansas have the right to hold local option sales tax elections. But our research also reveals that 82% of local option sales tax elections are held outside of general or primary elections. Sales tax increases in special elections have a much higher chance of passing, and voter turnout is very low in these elections.

The Arkansas legislature is currently considering a bill that would move most special elections to either general or primary elections. SB723 is designed to increase voter turnout by requiring special elections, such as sales tax elections, to be held at the same time as a primary or general election if there is one occurring in that year. For years that have no primary or general election, the bill also proscribes two specific dates on which these elections may be held. Under current law, cities and counties have a great deal of discretion as to when the election can be held.

Starting last summer, I began collecting data on sales tax elections in Arkansas along with one of my students at UCA, Alex Tatem. She and I have been able to locate data on over 900 sales tax elections in Arkansas going back to 1981, the first year local governments could hold these elections. We believe this is very close to the complete set of data.

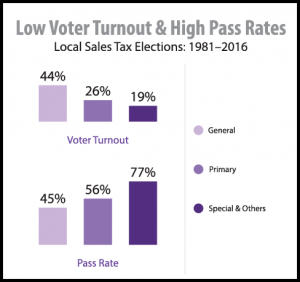

Of the over 900 elections, we found that 82% were held outside general or primary elections, and that these special elections had very low turnout, only about 19%. But the number of sales tax increases approved in special elections was extremely high, at about 77%. This contrasts with sales tax elections held during a general election, which were about 15% of the total. Only a small number of sales tax elections, 3%, were held during primaries.

During general elections, voter turnout was much higher, at about 44%. That is more than double the 19% turnout in special elections. And the number of tax increases that passed was much lower in general elections, with a pass rate of about 45%. Please download our one-page summary of data related to this issue, available in PDF format.

We also tried to provide some estimates of the cost of holding special elections, specifically for sales tax increases. This data was harder to find, but using data we found from a few large and small counties and cities, we estimate that all special sales tax elections since 1981 have cost a cumulative $7.4 million (in inflation-adjusted dollars). That is an average of over $200,000 per year. Keep in mind, though, that this is not simply the price of democracy. That is money that could be completely saved if sales tax elections were held to coincide with other elections, such as general or primary elections.

In summary, based on our research we predict that this bill would increase voter turnout, decrease sales taxes over the long run, and save local governments much needed revenue by having fewer elections. If the bill does not become law, local governments will continue to have the discretion to set election dates as they have since they were given the right to hold sales tax elections in 1981.